FIELD WORK EXPERIENCES – PSYCHOLOGICAL TEAM OF HCIT

Over the past nine months, the Psychological Team of HCIT has been providing services

of psychological help and support to the refugees from war-affected areas passing the “Balkan

route”, on the territory of Vojvodina.

The team for the psychosocial support made contact with over 120 refugees who

complained on different psychological concerns or someone from their environment recognized

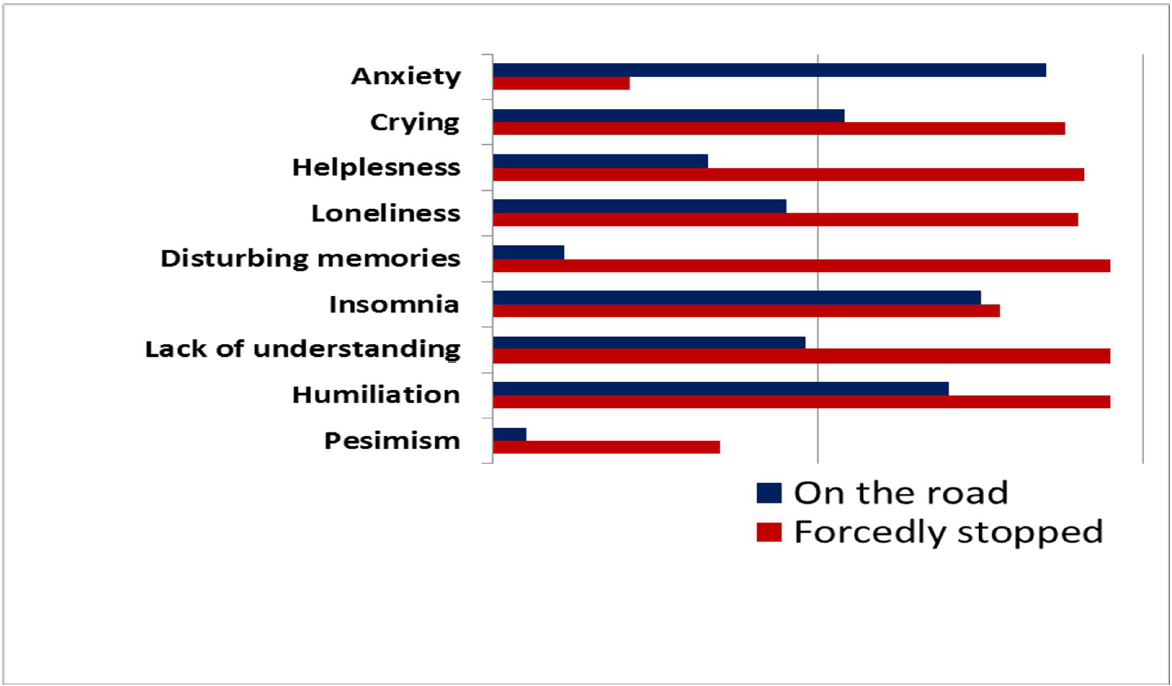

changes or unusual behaviors of them. While working with refugees, we have noticed

significant differences in the type of complaints and symptoms manifestation between those who

were “passing the route” and those who were forcedly stopped in their attempts to reach EU

countries. It is important to note that those who were forcedly stopped experienced more

complicated psychological issues that contributed to their additional traumatization – separated

families, illness or death of family members as the reasons for the forced staying, invalid

documentation that questioned the possibility of passing the borders and entering the EU,

inadequate conditions in the refugee camp, etc.

Within refugees who were “passing the route” we observed strong anxiety (fear related to

their goals and expectations), insomnia, occasional overwhelming emotions and uncontrollable

1 Activities and realization of this project were financially supported by the Embassy of the Kingdom of

the Netherlands. tears, and strong feelings of humiliation regarding the situation they are experiencing and

depending on other people’s help. On the other hand, those forcedly stopped on their way to EU,

manifested much more often severe depressive symptoms (helplessness, loneliness, feeling that

social surrounding have lack of understanding for their problems, and sadness), disturbing

memories of the recent traumatic events (i.e. flashbacks), followed by insomnia and (even

stronger) feeling of humiliation – comparing to the first group. Interestingly, despite all

adversities, even when being unable to cross the border – the vast majority expresses optimism

and hopes to accomplish their goals.

Our results, in line with recent research, points to the disturbing possibility that the

number of people who meet the criteria for mental disorders will significantly increase only after

they resettle in their destination country. This is even more likely, taking into account their

unrealistic expectations and envisions of their futures that might very soon turn into

disappointments.

Around 5% of refugees expressed need for psychological interventions. However, that

does not imply the absence of problems among the others or the lack of need for psychological

support. Apart from afore mentioned preoccupation with reaching the destination country and

dealing with existential issues (hence, suppressing traumatic memories), a considerable number

exhibit some of the symptoms but not recognizing it as something they should ask help for.

Hence, the fact that they are highly traumatized, place the refugees in a population with high risk

for developing disorder and furthering the necessity for prevention and first psychological aid.

Coping strategies and possibilities for applying “healthier” strategies (active attitudes are

healthier versus passive lamenting one’s fate and withdrawal, problem-solving orientation is

more useful than relying on other’s help or “drowning” the sorrow in alcohol, etc.) appeared to

mediate the symptoms onset. Those who have traveled with their families or within groups

rarely asked for help, as they received more support from their group and had more possibilities

for fulfilled and structured daily activities. Unlike them, lonely passengers (as by rule, men),

those separated from their families, were much more vulnerable. Those who frantically followed

news about the events in their country of origins have been chronically tense, while those who

felt that “all is in God’s hands” were calmer.

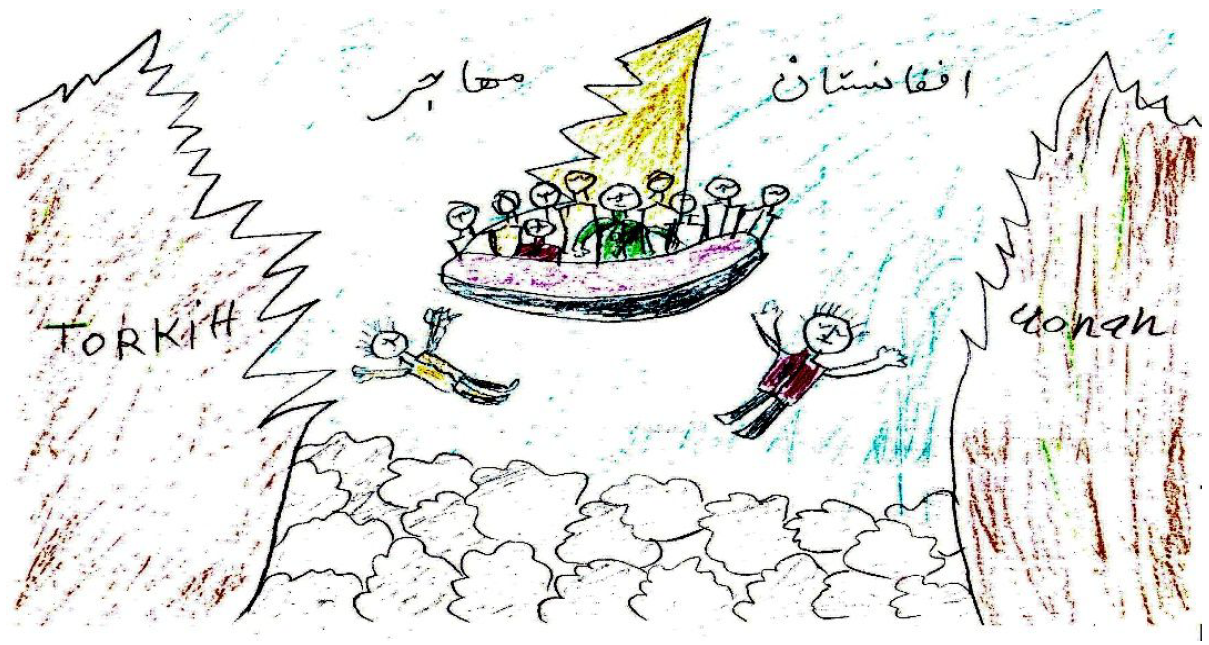

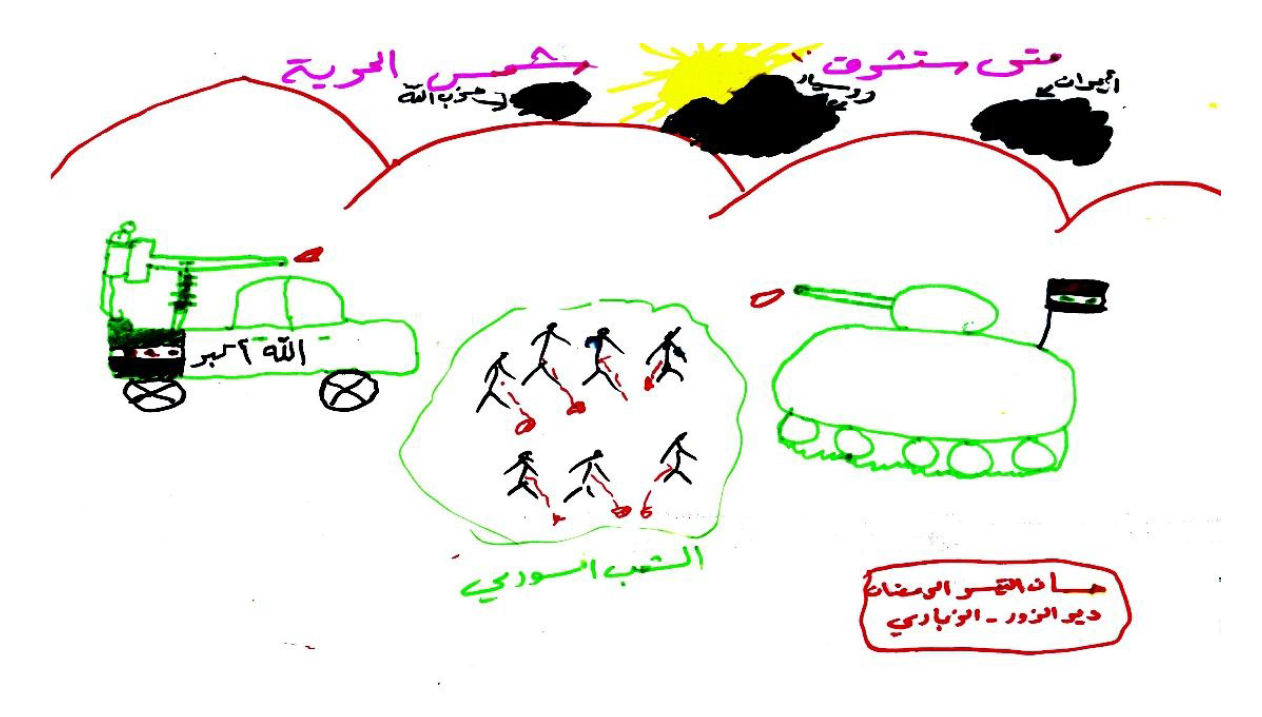

A special focus of the psychological team was on working with refugee children who

spend months on the road, in unhygienic conditions, often without the possibility of meeting the

basic needs (inadequate nutrition, lack of sleep, long sitting in vehicles or exhausting walking).

While working with children, we have noticed the different forms of behavior which

indicated the presence of emotional problems. Having in mind the conditions in which we

worked, drawings proved to be a fast and efficient way to communicate with children. In

cooperation with the Novi Sad Humanitarian Center (NSHC), we collected a large number of

children’s drawings that were used for qualitative analysis. In a sample of 354 drawings, 12% of

the total number were found to have clear indications of trauma (blood, murder, frightened faces

in the boat, people drowning), while in an additional 35% of drawings, indicators of high

emotional distress have been observed (tears on their faces, empty houses, people hidden in cars

without a face, ships at sea without people).

From these results, one can conclude that the drawings could be a quick and efficient way

of detecting children with traumatic experience and potential emotional problems as a result of

exile. In this way, help service providers can get a simple tool for making decisions about which

children have priority for getting psychological help.

In the following pages we present some of the drawings with the clear indicators of

traumatic experience.

Drawing 1. (Syrian boy, 10 years of age). Crossing Mediterranean Sea and two brothers drowned.

Drawing 2. (Iraqi girl, 7 years of age). People falling out from the boat and drowning in the sea.

Drawing 3. (Syrian girl, 9 years of age). Civilians (bleeding) in between the conflict between ISIS and

Drawing 3. (Syrian girl, 9 years of age). Civilians (bleeding) in between the conflict between ISIS and

Assad’s forces.

Drawing 4. (Syrian boy, 11 years of age). Broken photo frame portraying the family.

Drawing 4. (Syrian boy, 11 years of age). Broken photo frame portraying the family.

HCIT-Psychological-Field-Report.pdf (948 downloads )

Recommended Posts

Between Closed Borders

January 20, 2021